自2005年起,陈劭雄创作了一系列水墨录像作品,艺术家不断反思水墨画这一中国传统的绘画语言,作品《墨水东西》中,陈劭雄把日常的周遭的事物不知不觉地一一罗列,时间的形状随着景物的消失而慢慢显现,一连串生活中所触,所用,所拥有的事物,定义着我们存在的事物,一本护照、一个水龙头、一个胸罩和一本艺术杂志都在艺术家一丝不苟的描绘下传递出一种无常。在墨水系列作品中陈劭雄想表达的仍然是时间和物质的传统命题。用传统的水墨画反映现实的世界,并与新媒体技术的融合,是对传统文化在当下展示的可能性的有益探索。

在陈劭雄镜头下的各色各样的人、事、物,由集体按压指纹组成的城市标志性建筑风景图,亦或是城市风景与乖张图案的组合,这些熟悉而又陌生的场景观和事物,使陈劭雄发展出的这一套感知方式与叙事,带来的是在戏剧的,在全球化与城市发展背后,是关于“真实世界”的思考。

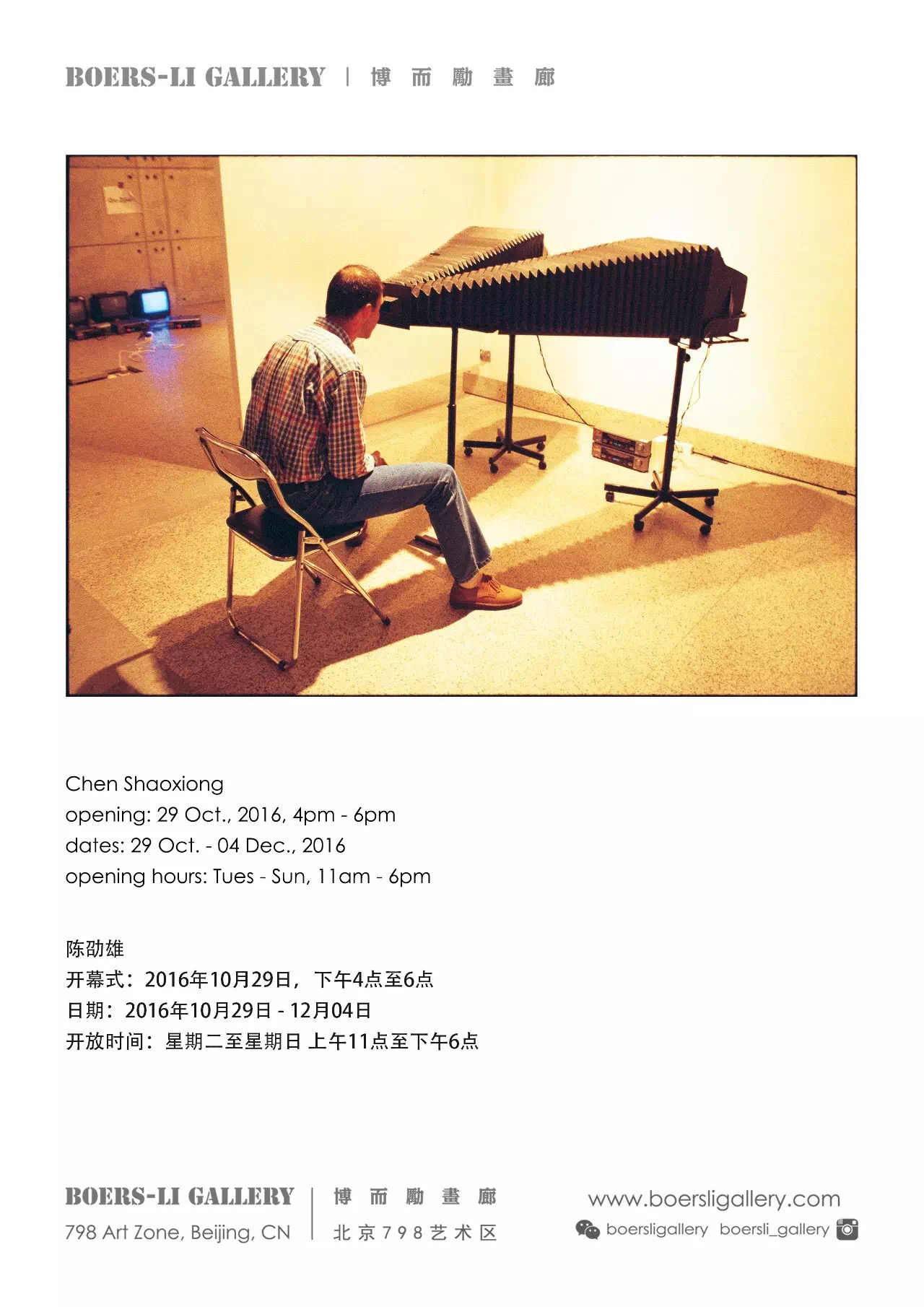

Boers-Li Gallery is honored to announce the opening of solo exhibition of “Chen Shaoxiong” on the 29th of October, 2016. This is Chen Shaoxiong’s 3rd solo with BLG, dating back his first exhibition “Visible and Invisible, Knownand Unknown” in 2007 and second solo “Seeing is Believing” in 2009. This exhibition will feature his works over 30 years of his career, with early installations, videos, photographys and works based on ink painting.

Chen Shaoxiong(born in Shantou, Guangdong) has been a driving force in the experimental art circle in Guangzhou since the early 90’s. Explorations in urban life of the most dynamic place in those days, Guangdong, have permeated his creative output since his early involvement with the “Big-Tail Elephant” group(Liang Juhui, Xu Tan, Lin Yilin). Acting as the creative “City Guerrillas”, members of this group maintained independence under collective action—intervening untypical development space within the city such as construction sites, streets, parkinglots etc. Over the past 30 years, Chen Shaoxiong’s profound engagment in the urban life and influential works has redefined the way people observe things.

Chen Shaoxiong’s thoughtful approach to research into the Chinese as well as western thinking positioned him as an explorer of conceptual reflection and contemporary art production. In 1991, he defined his position in the art world by taking a seven days period of silence to work himself in the format of aperformance and distance himself from painting. The works are meant to be aresearch in redefining space and time in relation to how perceive these dimensions. In Sight Adjuster, he uses two cameras to redirect theviewer’s eye, leading the eyes in two independent directions to two monitors that play related yet disruptive and incoherent scenes. The redirection of the eyes is challenging the mind of the viewer by forcing together various sequential streams of information. This procedure of”adjusting”changes the ways people see by putting into question our accepted ways of “seeing”. As the artist puts it: “what we see is not what we think, and what we want to see is not what we are meant to see.” Just like inhis other works, overlapping or sometimes disturbing imageries, may cause the first sight a sense of absurdity, at the same time generating an alternative way of interaction between social-cultural dynamics and the individual composure. This is dramatically visualized in the “Streetscape”series. In these series of photography and photographic installations, Chen Shaoxiongintermixes fragments of his daily life – sometimes very personal -with variousglobal urban scenes. He captures the changing landscape, or better to say “cityscape” into an imagery and collaging them to reconstruct a new, portable landscape.

This perspective shift on human activity plays throughout Chen Shaoxiong’s so-called “Ink video” in which he transforms traditional Chinese ink painting – concerningits subject as well as its technique – into contemporary animated video. In hiswork Ink Things, he categorizes his surroundings as a continuously changing decor in which typical scenes disappear as time passes. In this way the artist “portrays” our daily objects: a passport, a water tap, a bra or an art magazine etc. In these iconic “ink series”,Chen Shaoxiong stresses on the means of time and traditional materialistic proposition by using traditional ink painting to reflect on the current reality while integrating new media and technology.

Chen Shaoxiong has kept redefining the way of perception, and reflecting how the impact of time has exerted on individuals. The way of perception and narrating he develops—various people and things under his lens, a collective imagery of historical architectural sites reproduced by a series of finger pressing oncanvas, or the combination of city landscape and perverse images, brings the puzzling questions about the reliability of people’s perceptions towards the“real world”.