“九层塔:空间与视觉的魔术” 是一次跨界行动,是中国从未有过的展览方向和形式。它将邀请9位/组艺术家提供作品,作为展览的基础素材,同时邀请9位建筑师,9位设计师,组成九个临时团队。艺术家、建筑师、设计师三方联名合作,没有 “主次” 和 “中心”,只是分工与协作,最终形成9个全新类型的展览。

空间和设计是决定展览的核心元素,也是对展览和作品的再创作和再生产,它决定了观众看到什么,怎么看,看的次序和节奏。空间和设计,在这里不再是为展览服务,而是独立自主的体验,给予展览无数的变量和可能。

一直以来,我们缺乏一种高质量的跨界,它们不是流俗于明星和网红效应,迎合一种快餐式的出圈,就是自说自话,拘泥于专业壁垒。“九层塔” 倡导的跨界方式,创造了一个艺术、建筑和设计的连接点,一个全新的交叉学科,它既是三个专业间的实际需求,有益协作,又保留了各自的专长和优势,分工得当。

作为中国古代建筑,“塔” 有着一种特殊的结构,它的每一层讲述着不同的故事。这些故事和空间、设计,紧密围绕成一个彼此叠加的整体,成为展览的外在形象和精神内核。

“九层塔:空间与视觉的魔术” 由策展人崔灿灿和建筑师刘晓都共同在2020年发起,它是一个混合了思想、方法、工具的实践项目,也是对跨领域工作的兴趣班,拓展彼此方向的攻关小组。

“九层塔” 的出现,饱含着创造一个全新领域和事业的雄心,旨在发明一种新的合作方式和展览观念,重塑这个时代的感知体验。

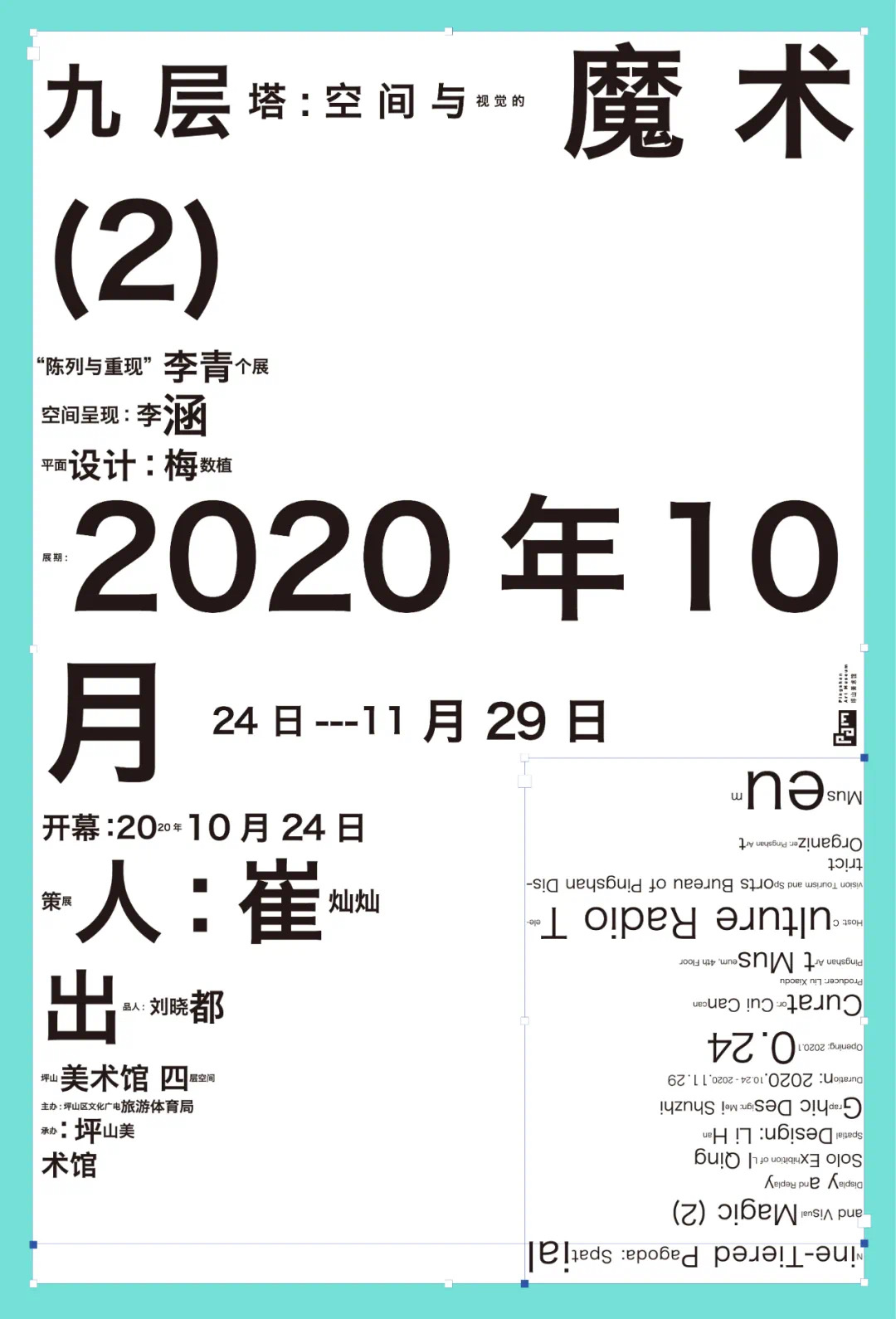

“陈列与重现” 李青个展

作为 “九层塔” 的第二个项目,“陈列与重现” 表明了艺术、建筑、设计的共同工作,也是整个展览追求的核心,如何陈列文本与视觉?如何重现思想和感知?展览以艺术家李青的作品为基础,邀请建筑师李涵进行空间呈现的创作,平面设计师梅数植进行海报等视觉系统的创作。

2019年,李青在上海荣宅的展览中,作品 “窗户” 和旧时宅邸有着别样的对话。重现的故事,似乎回到了往昔的昭华中,而《杭州房子》的陈设,却将殖民地的靡靡之音,片刻的温情记忆推回现实,一切荒诞、冲突。事实总是既不是这样,又不是那般的纯粹与戏仿,真实与复制。三年前,在香港,李青的 “灯光字” 与窗外的中环、六国饭店、东方大班,对面的九龙,有另一种奇妙的关系。电影里衡量香港房子的好坏,总看有没有窗,再往上是能不能看到远处,看到海。“窗” 在不同时空中陈列,有截然不同的状态和命运,它有时承载故事,重现希望,有时只是为了区隔距离。

选择李青,是因为这些作品和建筑、设计的关系,窗本是建筑的基本构件,是城市中的风景。它们因为 “艺术” 被观看,被体验和观察。又像这个展览的模式,“空间” 重现和陈列作品,“设计” 概括和重建文本。故事总被另一个故事描述,描述总被另一种描述 “目击”。

所有的窗户都有阶层,就像所有的设计都暗含一种立场。建筑师李涵和李青有着共同的契合点,对新旧建筑、城乡变迁、不同社会群体的关注。李涵将展场理解为一个即将拆光的建筑,在这片人为搭建的废墟中,新与旧,建筑群像和考古遗址记载着消失的历史。七彩的瓷砖,装饰的梦,你中有我,我中有你,说不清是在窗里看到城市,还是在这个城市看到你。

故事可以是各种故事。但无论是艺术家、建筑师还是设计师,都有差异之下的共性,一个同谋的工作重心:如何陈列和重现故事,如何观看事物的连接和转折?我们都深刻的理解 “修辞” 的意义。

策展人 崔灿灿

Nine-Tiered Pagoda: Spatial and Visual Magic, as a cross-disciplinary event, represents an unprecedented direction and form of exhibition in China. Nine (groups of) artists will provide their works as the basis material for the exhibition. Besides, nine architects and nine designers will also join to form nine temporary teams, hence the cooperation among artists, architects and designers. There is no ‘priority’ or ‘center’ in the exhibition, only division of labor and collaboration, presenting nine individual exhibitions of a brand-new type.

As the core determinant for the exhibition, space and design are also a kind of re-creation of the exhibition and the work; They determine the content and how the audience see the exhibition, as well as the sequence and pace. Space and design, no longer in the service of the exhibition, provide an independent and autonomous experience for the audience, granting the exhibition a myriad of variables and possibilities.

There has always been a lack of quality cross-disciplinary exhibitions, which are neither a fast food product preached by celebrities and online influencers nor a highbrow art confined to professional barriers. The cross-disciplinary advocated by Nine-Tiered Pagoda creates a nexus joining art, architecture and design together with a new cross-discipline, which reflects the practical needs and collaboration of the three professions, while it also retains the expertise and strengths of each with a proper division of labor.

As an ancient Chinese architecture, ‘Pagoda’ has a special structure, with each tier telling a different story. These stories, spaces, and designs are closely intertwined with each other into a superimposed whole, formulating the external image and spiritual core of the exhibition.

Nine-Tiered Pagoda: Spatial and Visual Magic, launched by curator Cui Cancan and architect Liu Xiaodu in 2020, is a hands-on project that mixes ideas, methodologies and tools. It’s not only a workshop for cross-disciplinary art, but also a platform for artists, architects and designers to cooperate and expand their development realms together.

The advent of Nine-Tiered Pagoda represents the ambition to create an entirely new field, with an aim to invent a new way of collaboration and to create a fresh exhibition concept that can reshape the perceptual experience of our times.

“Display and Replay” Solo Exhibition of Li Qing

As the second project of Nine-Tiered Pagoda, Display and Replay indicates the joint work of art, architecture and design, which is also the core of the entire exhibition. How do we display content and vision? How do we reproduce thoughts and perceptions? The exhibition is based on the works of Li Qing, with architect Li Han creating the space and graphic designer Mei Shuzhi in charge of posters and other visual designs.

In 2019, Li Qing held an exhibition at Shanghai Rong Zhai, where his work Window had a distinctive dialogue with the old residence, bringing the reenacted story back to the previous glory. While his display in Hangzhou House has fed the decadent sound of colonialism and fragmented memories of warmth to the reality, generating an absurd and contradictory mix. It’s hard to tell whether it’s true of parodic, real or replicated. Three years ago, in Hong Kong, Li Qing’s Neon Light Characters formulates a fictional interaction with the Central, Gloucester Luk Kwok, Oriental Taipan and Kowloon across the street outside his window frames. Windows are important metrics for the quality of house in Hong Kong movies. The best house should not only have windows, but the one where we can also see the distance, or even the sea through the window. ‘Windows’ are displayed in different times, with various states and fates. Some are carrying stories, some renewing hope and some just separating the distance.

Li Qing was chosen because of the relationship among his work, architecture and design. Windows are naturally part of a building. They themselves are also a kind of scenery. They are seen, experienced and observed because of “art”. They resemble the mode of this exhibition, with the ‘space’ replaying and displaying the work, while ‘design’ summarizing and reconstructing the content. The story is always told by another story, and the description is always “witnessed” by another description.

All windows have a class, just as all designs imply a stance. Similar with Li Qing, architect Li Han shares his concern for old and new buildings, urban and rural changes, and for different social groups. Li Han interprets the exhibition site as a building about to be demolished. In this man-made ruin, the old and the new, all the buildings and archaeological sites record the fading history. Colorful tiles are decorating a dazzling dream. All are mixed. We can’t tell if we see the city in the window, or if we see each other in this city.

Stories can have a myriad of versions. But no matter for artists, architects or designers, there is a commonality beneath the differences, or a complicity in the focus of work: How do we display and replay the stories and how do we view all connections and turns therein? We all have a deep understanding of what “rhetoric” means.

Cui Cancan, Curator